Opening November 13th

from 7pm to 9pm

Galeria Estação

R. Ferreira de Araújo, 625 - Pinheiros, São Paulo - SP

Artist

Writing my introductory text about Silva is both a pleasure and a challenge.

I’ve written a few before, always recounting how I first encountered his work and the artist himself. However, this exhibition, the second I’ve organized at Galeria Estação curated once again by Paulo Pasta represents a significant new milestone. It celebrates the traveling show that began last March at the Musée de Grenoble in France, launching the 2025 Brazil-France Cultural Year. This event featured a rich and diverse program dedicated not only to Brazilian visual arts but also to music, cinema, literature, circus, theater, dance, and other cultural expressions, and ran through September 30 in various cities across the European country. The same exhibition, titled José Antônio da Silva: Painting Brazil and curated by Spanish curator Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro, was on view for three months at the Fundação Iberê Camargo in Porto Alegre, beginning in August. Now, on November 15, the show arrives at the Museum of Contemporary Art of the University of São Paulo (MAC USP), expanded with works from the museum's own collection.

To contribute to this moment of recognition and celebration of Silva's work, Galeria Estação is opening a complementary exhibition featuring pieces from our collection, as well as from the collections of: Andre Mastrobuono, Breno Krasilchik, Gustavo Rebello, Ladi Biezus, Marcelo Noschese, Mauricio Buck and Orandi Momesso.

We invite everyone to visit both exhibitions currently on view in São Paulo, to discover works rarely or never before shown in the city by one of the most important Brazilian artists of the 20th century, Silva.

VILMA EID

I Am Silva

Since Van Gogh, we have all been self-taught painters, almost primitive.

As tradition nearly sank into academicism, we had to recreate an entire language.

And every painter of our time can recreate this language from A to Z.

No a priori criterion can be applied, since fixed rules no longer exist.

— Pablo Picasso (1)

In this quote, which I take as an epigraph, Picasso highlights Van Gogh as a great pioneer of modern art. It’s no coincidence that Van Gogh and Picasso were two of the artists most admired by the painter José Antônio da Silva. In fact, Silva considered himself, alongside them, the third genius of the trio. Exaggeration aside, I believe Silva's intelligence and intuition grasped the essence of that quote early on, whether he had ever actually encountered it.

Today, Silva occupies a very different position and reputation than he did decades ago. Many factors have contributed to this shift. Perhaps the most important is how his work continues to resonate with our time and new generations. He hasn’t become a dated artist. On the contrary, his work is continually reinterpreted, revisited, and exhibited. His painting has not withered over time. Quite the opposite. This positive reevaluation of his legacy confirms his rightful place as one of the great Brazilian painters, one of those who most significantly contributed to painting Brazil. (Not by chance, the major exhibition of his work held this year, touring both nationally and internationally, was titled Painting Brazil, a name given by its curator, Gabriel Pérez-Barreiro.)

I also believe that the current artistic trend, sometimes referred to as “identity art,” with its focus on expressing marginalized narratives, languages, and aesthetics has allowed us to reconnect with Silva’s painting and attribute new, contemporary meanings to it. Not that those meanings didn’t already exist, they’ve always been there. But as we know, each era brings new interpretations to reality.

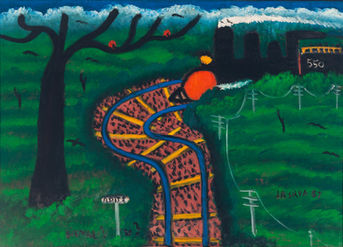

So, while I do think this cultural wave has favored Silva, I also believe the inherent qualities of his work have, by their differences, become more visible. Perhaps the clearest of these is that Silva never aimed for his painting to be merely a record of a given circumstance, or to serve a purely documentary or strategic function. His connection to reality is also invention, storytelling, and poetry. The past, his raw material, is continuously converted into a living creation. Even in works where denunciation and critique are most evident, Silva never let go of the how of painting: his awareness of the construction of the image was always paramount.

What I mean is that Silva, in his own way, internalized certain principles of Brazilian modernism, where form and content could not be separated without undermining the work’s sense of wholeness and harmony. The what to paint had to always be accompanied by the how to paint and if, in that, we see a Cézannian horizon, blended like in Picasso with a perhaps unconscious influence of African art, that wouldn’t be far-fetched. Silva always submitted his subject matter to formal synthesis, building with it an autonomous and ambiguous system, far removed from a simple visual record. These are the reasons why the label "primitive" seems so inadequate failing to account for the strength with which he turned lived experience into pictorial language. It seems to me that what mattered to him was not painting the life of nature but making painting itself come alive.

In the preface to Silva’s novel Maria Clara, the literary critic Antonio Candido wrote that the more the painter tried to give precise contours to reality, the more fantasy would burst forth. For Silva, then, reality and imagination could not be separated without compromising a full understanding of his work, without weakening its complete sense of form. This kind of fantastic realism also saved him from being a mere painter of rural customs, even though his recurring theme was life in the countryside: the heavy, constant labor; the memories of a fabulous childhood; a time when rural Brazilian culture still existed as a cohesive system, untouched by the eviction order of “progress.”

As I once stated, (2) perhaps the only kind of progress Silva was truly interested in was the internal progress of the work itself, the understanding of life’s transformative rhythm. This circumstance endowed his art with the quality of permanent becoming. For this reason, and for having lived it, Silva became the greatest interpreter of the metamorphosis of Brazil’s rural landscape: the replacement of native forest with farmland—an event both real and tragic—which he transfigured into poignant images and theatrical representations, a kind of anti-landscape, a stage where life and death enact their eternal drama.

At times, I also believe that the world’s growing ecological awareness—the recognition of the ongoing threat of environmental catastrophe—may have lent new meanings to his work. But I must emphasize: the greatness found in his painting could never arise from rhetoric alone. It had to be reached, first and foremost, through the autonomy of his visual language. In fact, I believe that by proceeding in this way using only the painter's own tools any latent critique gains even greater force.

When I curated José Antônio da Silva’s work for the first time at Galeria Estação in 2009, I titled the show: “I Was Born Wrong and I’m Right”, a phrase of his, which I had read in a text reproduced by Romildo Sant’Anna. At the time, this sentence struck me as especially fitting to describe a painter and a body of work that, in my view, were still somewhat clouded by hasty labels and interpretations by a critical legacy that cast him as a primitive painter, almost an outsider in the broader narrative of Brazilian art history. I am also fairly certain that this somewhat reductive view of his work was, in part, encouraged by Silva himself, who at times adopted this persona, presenting himself as the artist the system expected him to be.

By choosing that paradoxical phrase of his, I also aimed to frame his work in a different light believing that in art, hasty designations, hierarchies, and labels do little to illuminate the true meaning of a piece.

For this current exhibition, I’ve chosen a different phrase often repeated by the artist: “I am Silva.” Unlike the previous title, this one contains no ambiguity, it signals, for me, the new position he now occupies. It is a declaration, an affirmation and reaffirmation of his place in the present.

He loved introducing himself this way, repeating his surname, the most common and popular surname in Brazil, as a way of marking his presence. In the beautiful documentary about him made by Carlos Augusto Calil (3), we see him repeatedly stating it, with unmistakable self-assurance: “Who doesn’t know Silva? I’m Silva!”, “Silva is rural life…”, “Nature is my God, and I am Silva!”

I think more of a feeling of joy, born from the recognition of the source of his poetry and inspiration. These phrases could also serve as captions to his self-determination, his boldness in producing a body of work stripped bare, without the safety net of any formal training.

His work, like that of many masters surpasses him and is ahead of him; and like theirs, and because of this very quality, it seems to want to reinvent painting itself. What I mean is that he learned from himself. An ethics and an aesthetics shaped by someone who absorbed the hard lessons of labor and life experience and managed to give them form and expression.

Read quickly, these phrases might seem to suggest that he was giving himself the airs of being the voice of nature and its interpreter. But I don’t believe there was any pretension in this context.

This exhibition does not aim to encompass the entirety of the painter’s themes and content. That would be a task more fitting for museums and historians. But it does aspire to show everyone some of the most important aspects of his production, without favoring specific dates or periods through a carefully selected group of paintings.

I hope they can attest to the greatness of his work and beyond that, reignite our own sense of belonging, reminding us that sophistication, quality, and popular origins can and should coexist in the history of art.

Paulo Pasta

Notes

-

Françoise Gilot and Carlton Lake. Life with Picasso. São Paulo: Samambaia, 1980.

-

My text for the catalog I Was Born Wrong and I’m Right. São Paulo: Galeria Estação, 2009.

-

Who Doesn’t Know Silva – documentary filmed by Carlos Augusto Calil. São Paulo, 1979.

His work, like that of many masters surpasses him and is ahead of him; and like theirs, and because of this very quality, it seems to want to reinvent painting itself. What I mean is that he learned from himself. An ethics and an aesthetics shaped by someone who absorbed the hard lessons of labor and life experience and managed to give them form and expression.

Paulo Pasta

TOUR VIRTUAL

About the artist

José Antônio da Silva

1909, Sales de Oliveira | SP - 1996, São Paulo | SP – Brazil

José Antônio da Silva was born into a poor family in Sales de Oliveira, São Paulo, Brazil. His oil canvases were first noticed by São Paulo art critics in 1946 at a small town-hall art competition in São José do Rio Preto, in rural São Paulo State. Due to the critics’ interference and much to the horror of the local organizers, first prize was nearly handed to the unknown self-taught artist who painted over flannel-fabric stretched frames in a “garish” color scheme, avoided smooth brushstrokes and refrained from religious scenes. Eventually, da Silva placed fourth in his hometown competition but soon gained the approval of Professor Pietro Maria Bardi, MASP Museum’s renowned founder-director, who included him in his 1970 book “Profile of the New Brazilian Art.” Soon he was showing solo in São Paulo’s most prestigious gallery of the 1950s, Galeria Domus.

I am Silva - José Antônio da Silva

Opening: November 13th at 7pm

From November 13th to December 23th

At Galeria Estação

Address: Rua Ferreira de Araújo, 625 - Pinheiros - São Paulo-SP

Phone: 11 3813-7253

Visits: Monday to Friday: 11am to 7pm | Saturdays: 11am to 3pm

Directors

Vilma Eid

Roberto Eid Philipp

Curator and Art Historian

José Augusto Ribeiro

Commercial Director

Giselli Gumiero

Sales

Amanda Clozel

Alyne Shiohama

Production

Lu Mugayar

Marketing Director

Luciana Baptista Philipp

Communication and Marketing

Zion Branding

Photos

Philip Berndt

Assembly

Cadu Pimentel

Lighting and production support

Marcos Vinicius dos Santos

Kléber José Azevedo

Diogo Gabriel Leite Santos

Press office

A4&Hollofote Communication

Revision

Otacilio Nunes

Translation

Maria Fernanda Mazzuco - English

Printing and finishing

Romus Graphic Industry